Barrows: A Beginner's Guide!

Unsung Heroes of Early Bronze Age Britain

Welcome to my April newsletter, which this month focusses on a class of prehistoric monument that, in my opinion, attracts far less acclaim than it deserves: the Bronze Age burial mound, or ‘barrow’.

If you’ve spent any time in rural Britain, you’ll be familiar with these grassy mounds, which we Welsh refer to as ‘twmps’, and which on OS maps are labelled as ‘tumuli’ (as they were known to the Romans). In parts of Dorset, the South Downs, Lincolnshire, the chalklands of Wessex and north Yorkshire, there are literally hundreds draped over ridges, clustered in fields or standing enigmatically on the tops of prominent hills. Further west and north, in regions where the soil is thinner, they are replaced by piles of stones, or ‘cairns’.

I first developed an interest in them back in the mid-noughties while researching a book of walks for the Ramblers that culminated in great viewpoints accessible only on foot. It was amazing how many special spots were crowned by barrows and cairns, as if our ancestors were responding to precisely the same qualities of landscape that appeal to us today (which of course was unquestionably the case).

What I didn’t appreciate back then was that these mounds nearly all originated in a specific and very important period of prehistory, when these islands were being colonized by incomers from what we now know as the Low Countries (the Netherlands, Belgium and northeastern France). Nor did I understand the subtle ways in which the structures related to the wider landscapes. Not until I started photographing them from the air did I realize barrows were keys capable of unlocking hidden geographies and long forgotten connections between places.

Now I’m more drawn to these sites than any other type of prehistoric monument, both because they frequently make great photographs, and because they invariably present a puzzle. Work out why a mound or Bronze Age cemetery occupies the position it does (which may not always be immediately apparent at ground level) and you’ll discover something important about that patch of land and what surrounds it. Those eureka moments are truly wonderful, connecting you in a vivid way with the people who inhabited Britain 4,000 years ago, and unlike physical treasures, such insights don’t require any digging!

But first, some context . . . .

When were barrows made?

The oldest round mounds in Britain date from the Neolithic period, but the ones I’m particularly interested in date from a millennium later, in the Chalcolithic (‘Copper Age’) and Early Bronze Age. Around 2,400 BC (the time of the final phase of Stonehenge), the British landscape began to acquire large earthen barrows containing both inhumations, in the form of crouched burials, and cremated remains contained in elaborately patterned pots, or ‘beakers’.

DNA analysis has shown that the people interred in these structures shared a very different ancestry from their Neolithic neighbours – one originating in the Pontic-Caspian steppe way to the east. With their fairer hair, paler eye colours and complexions, these newcomers – known to archaeologists as ‘the Beaker Folk’ after their decorated funerary urns – heralded the arrival of metal working in Britain, along with what appears to be a new set of beliefs, ritual practises, and styles of weapons and dress.

Beaker graves often contained an array of luxury goods, perhaps deposited as honorific gifts or to accompany the deceased on their journeys to the afterlife. These ranged from beautifully crafted and decorated copper knives to fancy polished stone maces, finely made tools, archery kit (notably writs guards and arrowheads), cast bronze axes and items of personal jewellery made from exotic substances such as amber, jet, faïence and even gold.

Burial mounds continued be built until roughly 1,100BC, when the practise became less widespread, disappearing altogether by the Iron Age.

How were they built?

In their simplest form, round barrows were piled up using earth excavated from a surrounding ditch. Sometimes, they were more structured, with alternating layers of stone and soil, or occasionally turf stripped from nearby pasture or heathland. Pollen analysis from these have enabled archaeologists to reconstruct the mix of plants that predominated in the landscape at the time the barrow was built.

Were there different types?

Round barrows from the Early Bronze Age are classified into to five main types: bowl, bell, disc, saucer and pond. Some of the larger cemeteries in upland areas of chalk or limestone hold several of these varieties, but no correlation has thus far been made between the form of mounds and remains interred within them. Some contained a single person; others, the bones or ashes of several people inserted at dates after construction of the original mound. Men, women and children were sometimes buried together.

What factors determined their placement?

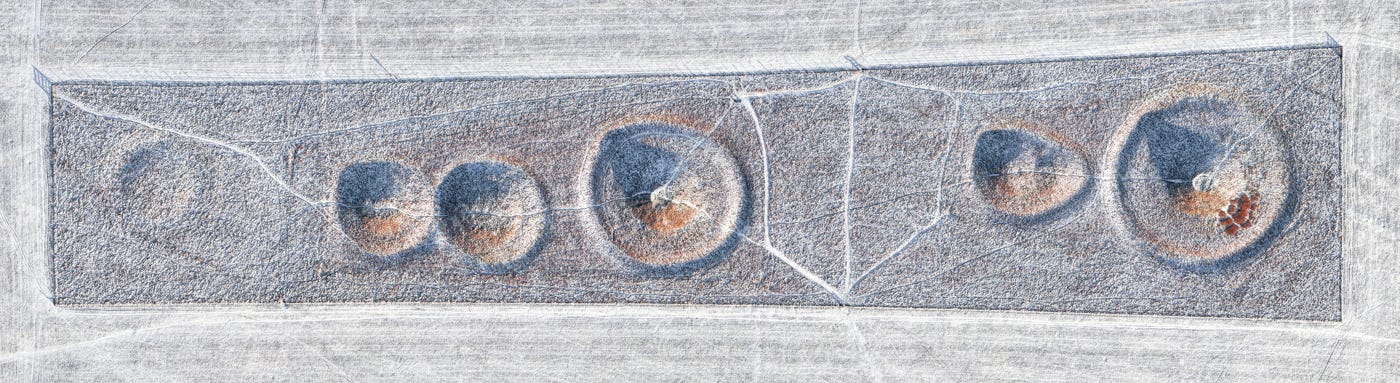

The above image shows an Early Bronze Age barrow cemetery outside the village of Lambourn in Berkshire. It sits on a valley floor flanked by rolling farmland and race horse gallops.

This kind of shallow valley is typical of the region and at first I couldn’t work out why it had been selected as a burial ground. Once the I got the drone in the air, however, it became clear that the proximity of the chalk stream flowing must have been a factor.

Later, I consulted a river map of southern Britain and noticed this stream – the eponymous River Lambourn – flowed southeast through a long and prominent valley to join the River Kennet at Newbury, which later joins the Thames at Reading. Thus the Lambourn formed one of major tributaries of southern Britain’s principal waterway, winding from the fertile chalk uplands to the sea.

This, of course, would have been common knowledge back in the Bronze Age, but today the connection of the Lambourn with the Thames is largely forgotten.

The source or confluences of important rivers were often the focal point of cemeteries from this era. So too were sink holes, cavities worn in the bedrock by rain water. These strange ‘dolines’, as they’re known by geologists, clearly fascinated our Bronze Age ancestors, perhaps because they were seen as liminal places – portals to the Underworld, where chthonic deities entered and left the land of the living.

Two striking examples are to be found in Dorset, on the Ridgeway at Bronkham (near the Hardy Memorial; above) and Poor Lot to the west of Dorchester.

It seems the Beaker folk also continued to venerate the places sacred to their Neolithic predecessors. One of Britain’s largest concentrations of barrows, for example, is to be found on the high ground overlooking Stonehenge. The wealth of grave goods discovered in the vicinity (notably the famous ‘Bush Barrow’ to the south of the stone circle) suggests the area may have been reserved for high-status burials.

Where did the practise of barrow building originate?

Dotted across the grasslands of Central Asia and Eastern Europe are a collection of great burial mounds known as ‘kurgans’, which, although erected many centuries before, bear more than a passing resemblance to British barrows. The similarity is not coincidental. Descendants of the kurgan builders expanded into northwest Europe during the first half of the third millennium BC, eventually crossing the channel around 2,500BC, bringing with them their ancestral tradition of piling up mounds over graves. These newcomers are also believed to have introduced metal making to Britain and, according to recent DNA research, the gene responsible for lactose tolerance.

Were barrows always as ignored as tend to be today?

Barrows were widely robbed in the Medieval era, but it wasn’t until the late 18th and early 19th centuries that the mounds became the focus of more serious antiquarian investigation.

The Wiltshire duo, William Cunnington and Sir Richard Colt-Hoare, excavated hundreds across Salisbury Plain in the first decade of the 1800s, meticulously conserving the grave goods they found in them during their excavations (though sadly not the bones). General Pitt Rivers introduced a more systematic approach in later decades, but it was Leslie Grinsell (1907-1995) who conducted the first comprehensive survey, visiting and recording the locations of around 10,000 barrows across southern Britain – a monumental endeavour conducted almost entirely by public transport, bicycle and on foot. It was Grinsell who first noted the similarity between British pond barrows and the palisaded mounds of the Netherlands.

Which are the best barrows or cairns to visit?

Here’s a rundown of some of my favourite Bronze Age barrow and cairns sites in Britain. You’ll find lots more on my website and in my forthcoming book, The Aerial Atlas of Ancient Britain (published by Thames & Hudson at the end of the summer – more on that below!)

Stonehenge, Wiltshire

The greatest collection of barrows in the UK is to be found in the fields around Stonehenge. Normanton Down, immediately south of the circle, holds a particularly impressive array, including the famous Bush Barrow (whose treasures are on display in Devizes Museum). To the east, the spectacular King’s Barrows adorn a wooded ridge with a great view of the stones, while to the east, the Winterbourne Crossroads cemetery is also worth a visit. My personal favourite, though, is the beautiful Cursus Barrow group (above), fifteen minutes’ walk north of Stonehenge towards Larkhill army camp.

Oakley Down, Dorset

Sliced by a Roman road, this cemetery on Cranborne Chase in Dorset holds all five barrow types: a full flush! It’s on private land but easily accessible from the main road and via the public footpath running along the route of the Ackling Dyke.

Poor Lot, Dorset

Difficult to access, but truly spectacular from the air. The elevated vantage point reveals the connection between the barrows, sink holes and likely location of a long disappeared river confluence (now over-laid by roads).

North Hill, Priddy

Two rows of large burial mounds flank an area of high bog in the Mendips, close to the village of Priddy – one of Britain’s great Bronze Age spectacles.

Lambourn, Berks

Grinsell is credited with discovering this wonderful barrow cemetery in West Berkshire, which sits at the head of one of the Thames’ tributaries amid bucolic chalkland scenery.

Foel Drygarn, Pembrokeshire

This trio of enormous cairns presides the high moorland from where the famous ‘bluestones’ erected at Stonehenge originated.

Kilmartin Glen, Argyll

Scotland boasts a rich array of stone-built cairns in a variety of styles, but these, in a secluded glen to the south of Oban, are the pick of the crop.

News

The ‘Big News’ this month is that after more than three years of travel, research and writing, work on my book is finally complete! It’s on its way to the printers now and will be published on time at the end of the coming summer. Here’s a sneak peek of the cover. I’ll be sending out information soon on how you can pre-order a signed copy directly from me (if you haven’t already via my Crowdfunder last summer).

Exhibition

We’re already into the final month of my show in Salisbury Museum, so if you’re intending to pay a visit, better get your skates on! The reaction has been amazing. Thank you to everyone who’s written to me to say how much they enjoyed the prints, and a special extra-big thank you if you bought one of them while you were there. Every penny helps keep the wheels of this chariot turning.

Thank you!

I hope you enjoyed this whistlestop intro to the Barrows of Britain. You’ll be able to find out lots more on the subject in my book, which has a big fat section on burial mounds.

I’m about to leave for sunny Dorset to make the most of the lovely weather we’re enjoying this Easter weekend. Top of my shot list is an Iron Age sea fort on the Jurassic coast, and a fantastic barrow site I only recently discovered on the military range near Lulworth (which I’m hoping will be nice and quiet while I’m there!). Look out for the results on Instagram over the coming week.

Thanks for reading to the end of this newsletter! Wishing you a restful Easter . . .

David

Wonderful!

I had no idea you were on Substack, I've been following you on IG for years, so to find you here was a breath of fresh air. Looking forward to reading more. Your writing is as beautiful as your photography.

Very helpful guide, thank you!