Dolines and the Dead: Gateways to the Underworld?

Sink holes clearly held great fascination for our ancestors, who often created funerary and other ritual sites beside them.

What do all of the following prehistoric sites have in common? Here’s a clue: it’s to do with water. Or rather, water disappearing underground.

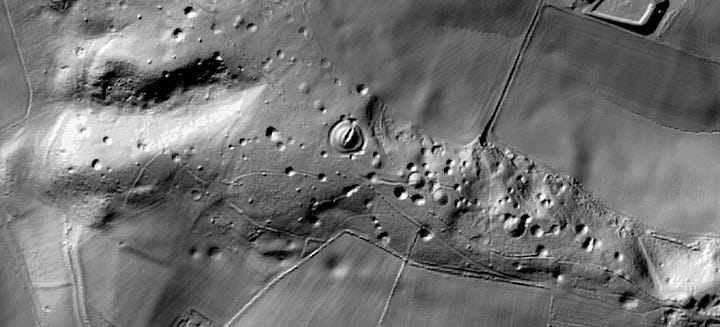

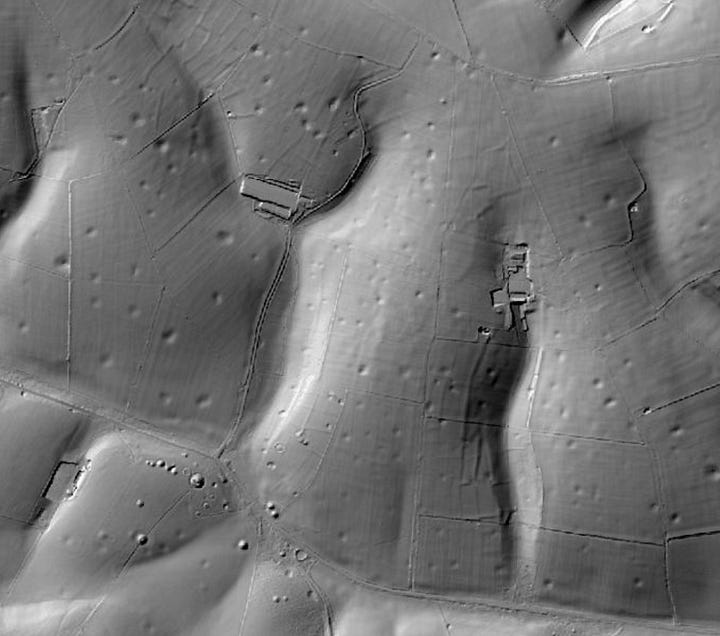

The answer is that they were all created because of their proximity to sink holes, also known as ‘dolines’, or ‘swallets’ – cavities in alkaline bedrock formed by the action of acidic rain water. Prehistoric people were clearly fascinated by them, as we can see from the number of ritual sites located in areas where sink holes were numerous.

Like us, our forebears would have wondered what these mysterious hollows were. They probably believed they were portals of some kind, where ancestral spirits or chthonic deities were able to enter and leave the world of mortals. Maybe this explains why, around 3,000 BC, Neolithic herders on the Mendip Plateau in Somerset created a complex of four giant circles in an area pock-marked by swallet holes. The water drained through them into an invisible river which flowed underground to emerge three miles away at the mouth of Cheddar Gorge.

In the Neolithic period, people placed polished stone axes, flint tools and pieces of pottery into the holes as votive offerings t. The artefacts lay undisturbed for thousands of years, mingling with the bones of long extinct animals such as cave lions, hyenas, bear, aurochs and reindeer, who had fallen (or been chased by Mesolithic hunters) into them.

It’s likely rituals performed at the circles would have enacted origin myths associated with the site and its mysterious openings in the earth, which in certain weather conditions allegedly emit eery gurgling and moaning sounds.

Elsewhere on Mendip, vertical shafts formed by natural erosion were occasionally used for the deposition of human remains. The most striking example was Charterhouse Warren near the head of Cheddar Gorge, in which the bones of 37 individuals were discovered in 1972. They had been deliberately killed (just under half by blows to the head), their bodies decapitated and hacked to pieces, before being partially consumed (by chewing, the researchers concluded) and thrown into the 15-metre-deep pit – an act of violence unique in the anals of the British Early Bronze Age.

DNA analysis of the bones revealed evidence of infection in two skeletons belonging to children by the pathogen Yersinis pestis – a forerunner of bubonic plague - leading some archaeologists to conclude this had perhaps been a massacre of a community infected with the disease.

More typical of the Early Bronze Age are two rows of beautiful burial mounds created on high ground overlooking Priddy Rings (and their numerous swallet holes). The North Hill and Ashen Hill cemeteries exemplify how Early Bronze Age people who migrated into Britain in the last few centuries of the third millennium BC often revered the same sacred sites as their Neolithic predecessors, especially in cases such as this, where they were associated with water.

The most extraordinary examples of Bronze Age barrows sited close to dolines, however, lie along the South Dorset Ridgeway, just south of Dorchester. Here, just over 400 burial mounds adorn a high whaleback ridge riddled with natural cavities and depressions. On Bronkham Hill, close to the Hardy Monument, many of these are of a comparable size to their adjacent barrows, leading some archaeologists to believe that the mounds were intended inversions of the swallets, like giant jelly molds.

We can never know for sure what our ancestors believed these geological oddities to be, but we do know from their frequent association with ceremonial sites dating from both the Neolithic and Bronze Age that they were important.

The photo ibelow shows the beautiful barrows of North Hill, near the village of Priddy, under a dusting of snow. The image features on my new 2026 calendar, along with eleven other of my favourite shots from the past year. Signed copies are available direct from my studio here.

News

The big news here is that yesterday I signed a deal with the publisher Profile for my next book, which will a travelogue exploring some of the wondrous ways people in Neolithic and Bronze Age people used landscape in their ceremonial monuments. The project has been a few years in the making and I’m greatly looking forward to getting stuck in to the writing soon. More details to follow!

I’m also doing a talk on the 27th November, at the village of Child Okeford in Dorset, near one of my favourite sites in Britain: Hambledon Hill. Hambeldon will feature prominently, as will the marvels of nearby Cranborne Chase, including the Dorset Cursus. You can book tickets here.

Thanks for reading to the end of this piece. If you enjoyed it, please ping me a like and share with friends and family members!

As a geotechnical engineer I have had many experiences with sinkholes in Southern Africa. There is so much prehistoric remnants in the quieter regions. Growing up in Britain and studying geology, the history of early humans is all around. I still think the stone circle in the playground of a Tesco is my worst example of the care of this history. Your article is excellent and stimulates further understanding of our ancestors. Great work

Good stuff!