A belated happy Imbolc!

First off, an apology. Those of you who follow me on social media may be aware that I’ve had a challenging few months. Last October I developed a heart problem, quite out of the blue, and after seven scary weeks wondering if I’d make it to Christmas found myself on a cardio ward for an emergency procedure. The op went well and I’ve since made a full recovery, but the enforced period of idleness left me with a bit of a writing backlog to deal with. The book I’ve been working on for a year and a half had been reaching its end phases and that, combined with an avalanche of calendar orders over Christmas, put my newsletter schedule into arrears. But fear not: I intend to make amends with more frequent posts over the coming few months!

Thank you everyone for your patience and support. Writing this gives me enormous pleasure and I hope will it provide some inspiration for the coming spring.

Suitably enough given the nature of my recent health crisis, the subject of this week’s newsletter is one close to my heart. The Mendip Hills of Somerset, where I live and work, is also where I spent my formative teenage years back in the 1970s and 1980s. At that time, before the era of Minecraft and mobile phones, exploration of the old droveways, cave systems, woods, combes and high moors of the plateau was how my mates and I filled our Sundays. In the course of our wanderings, we encountered many prehistoric burial mounds, huddled in rain-soaked pastures and amid the bracken of Black Down, and wondered how, when and by whom they might have been made.

With no grounding in archaeology (history seemed to start with the Romans as far as our teachers were concerned), none of us knew that the long barrow we’d climbed over in Priddy was Neolithic, or that the rows of round ones on nearby North Hill dated from the Bronze Age, nor indeed when these eras started and ended, or why any of it might have mattered. We didn’t realize the significance of the bones and stones unearthed in the sediment of caves at Cheddar Gorge, Burrington Combe and Banwell, which we slithered around in filthy boiler suits. But in a funny way, we definitely did feel the breath of the ancestors on our backs as we pedalled and trekked along those wet lanes, our welly boots clagged with Mendip clay.

Living with those enigmatic vestiges planted seeds that have since flowered into something I could never have imagined in my youth: a form of photography that would have seemed space age to the 13-year-old me.

These past few years I’ve returned with my drone to the sites I remember from my school days, and discovered many others I never knew existed. I’ve read everything I can get my hands on about them and been lucky enough to correspond with the archaeologist Jodie Lewis who knows more about the region’s prehistory than anyone else (more on her later), which has given me a whole new perspective on an area I love and which I now enjoy spending time in with my own teenage children (who are regrettably rather more enthused by Minecraft than Bronze Age burial mounds!).

Here, then, is a rundown of my favourite prehistory hot spots on the Mendip Plateau, presented in roughly chronological order, with tips on access them and a roundup of places you see the extraordinary artefacts found at and around them.

Cheddar Gorge

Synonymous with the gimcrackery of the show caves and cheese emporia, Cheddar Gorge has in recent years been a victim of its own stupendous, craggy beauty. Few of the daytrippers stumbling around the slippery clifftops, however, are aware that they are treading in some very old footsteps indeed. Bi-facial flint tools, dated to 400,000–480,000 years ago, have turned up in a quarry at nearby Westbury-Sub-Mendip, along with the remains of exotic, long-extinct woolly mammoth, rhinos, lions and hippos.

The headline finds in the area, however, date a more recent, warmer interlude at the end of the last Ice Age, which began abruptly around 12,700 BC. Within an amazingly short time (perhaps as little as twenty years), hunter-gathers from what is now France appeared in the region, following the horse herds north and setting up camps in Cheddar Gorge.

Gough’s Cave, on the east side of the defile, has yielded a particularly rich storehouse of artefacts from this period of the Upper Palaeolithic, including decorated tools made from red deer antler (believed to have been used for making rope and string), elaborately engraved rib bones and pebbles, and the earliest traces ever found in Britain of domesticated dogs.

The well-preserved skeletal remains of two adult humans and two children were also uncovered here. Microscopic analysis of cut and scrape marks on the bones has revealed the corpses were expertly skinned and butchered shortly after death. Eyes, tongues and brains were removed, and some of the larger bones cracked open to expose the marrow.

Some have interpreted this as evidence of cannibalism, for which parallels exist in modern times among groups in the Highlands of New Guinea. Others have pointed out no hard proof actually exists for the consumption of human flesh at Gough’s Cave, and that the excarnation and bone breaking could just have plausibly been a ritualized way of disposing of, and venerating, the remains of loved ones.

Nowadays a gaudily-lit grotto owned and managed by the Longleat Estate, Gough’s retains little of the atmosphere you might hope for from a site of such rich archaeological importance, while the cream of the artefacts found inside it are on display elsewhere (see below). But knowing this landscape hosted bands of horse hunters nearly fifteen-thousand years ago gives the gorge walk a novel edge. This was one of only a tiny number of places in these islands we know for sure humans inhabited during the Ice Age, and which people continued to occupy for many thousands of years afterwards. A fossilised male skeleton found in Gough’s Cave (so-called ‘Cheddar Man’) has been radio-carbon dated to 7,100 BC - the early Mesolithic period - with DNA tests suggesting the individual had dark-brown skin, blue eyes and wavy black hair. When volunteers from the local village gave DNA samples for testing, a geography teacher at the local secondary school turned out to be a direct genetic descendant!

Access

Gough’s Cave has been closed through the pandemic but will re-open to visitors on April 1st. A selection of objects discovered in it are displayed at the small site museum. The rest may be viewed at the Balch Gallery on the ground floor of Wells Museum (www.wellsmuseum.org.uk) - except for the ‘Cheddar Man’ skeleton, which resides in the Human Evolution Gallery of the Natural History Museum in London.

Aveline’s Hole

Human settlement around the Mendip Plateau ceased with the return of cold conditions at the tail end of the Ice Age, roughly 11,000 years ago. When this freeze ended, Mesolithic hunter-gatherers re-occupied the region, pursuing wild horses, red deer and auroch.

In addition to a massive quantity of flint flakes, blades and arrow heads scattered at temporary camp sites across the uplands, a unique hoard of human remains from this period has been discovered at Aveline’s Hole, a cave in Burrington Combe, on the north side of the Plateau.

Unlike at Gough’s, the cavern does not appear to have been inhabited. Instead, it was used as a kind of tomb, where bodies were ceremoniously laid to rest, some covered in tufa stones found at local springs, others adorned with perforated horses’ teeth, fragments of ammonite fossils and red ochre. One had a piece of a child’s skull placed on her shoulder. A stalagmite had formed on another. Engravings have also been identified on the walls of the cave, which is nowadays locked to protects its prehistoric rock art.

In total, more than fifty different individuals are represented in what is often described as ‘Britain’s oldest cemetery’. While much of the skeletal material was lost when a Luftwaffe bomb destroyed the museum where it was displayed in 1940, enough survived to be able to carry out modern radio-carbon dating tests and DNA analysis.

The results were significant. Firstly, they confirmed a very early date of 8,300–8,500 BC for the Mesolithic bones. Recent DNA tests on the Aveline’s Hole material have also revealed this influx formed part of a wider population movement originating in southeast Europe and the Near East, starting around 12,700 and which reached the periphery of northwest Europe in the 9th and 10th millennia.

The Priddy Rings

Some debate surrounds these enigmatic circles near the village of Priddy. There are four of them, ranging from 185 to 194m (607 to 636ft) in diameter. Three are laid out on a single axis, while a fourth, further north and seemingly detached from the others, is a little out of kilter and now virtually invisible.

Strictly speaking they are not ‘henges’ (because their ditches lie outside their banks). Archaeological work carried out by Jodie and her team, however, has shown they were carefully constructed, with inner cores of stone piled between fences of wooden hurdles and posts, which suggest the earthworks were probably more than mere livestock enclosures.

Recent carbon dating of organic material found at the bottom of the ditches has placed the rings at around 3,000 BC, which makes them roughly contemporary with the first Stonehenge circle. Quite why four were created so close together is less certain, but the choice of location, in a natural amphitheatre surrounded by low hills, would seem to be connected to the presence among them of numerous swallet holes or ‘dolines’ – cavities eroded in the limestone bedrock by rain. The acidic water percolates downwards through invisible cave systems, eventually joining the subterranean river that flows beneath nearby Cheddar Gorge.

There can be little doubt our Neolithic ancestors were aware of this topographical connection, and that they must have been fascinated by the mysterious holes, which have yielded evidence of sacrificial offerings as well as the bones of long-extinct animals, including lynx, rhinoceros and mammoth, whom we know were hunted in the inter-glacial and later Mesolithic periods by inhabitants of the caves at nearby Cheddar Gorge and Burrington Combe.

Access

Access to the site, which lies on private land, is prohibited today, but, in truth, there’s little to see at ground level. The grandeur of this extraordinary piece of ancient land art can only be fully appreciated from the air.

Gorsey Bigbury

Tucked away at the head of a side valley above Cheddar Gorge, this diminutive earthwork attracts little attention, yet when it was excavated in three separate digs before World War II the monument yielded the largest single hoard of prehistoric artefacts ever discovered in the region, including around 4,000 worked flints and a huge quantity of animal none, charcoal and Beaker-period pottery, representing an estimated 100 to 120 vessels.

Sadly, the finds were lost when the building in which they were kept took a direct hit from a Luftwaffe bomb in World War II. But the drawings from the archaeological report survive and indicate the site was probably created in the Neolithic period, but saw a period of intensive use in the Early Bronze Age.

The monument, classed as a ‘henge’ by archaeologists, comprises a ditch cut into the limestone bedrock, with a causeway entrance to the north and a platform of compacted stone in the centre. Screened today by woodland and on private pasture, it is not easily accessible and lacks the outlook it may once have enjoyed, but must have been a prominent landmark for the communities of herder-farmers who inhabited these uplands four- to five-thousand or more years ago.

North Hill: the Priddy Barrows

At around 300m (1000ft) in altitude, North Hill near Priddy is among the highest points in the Mendips, thus closer to the sky and heavens than any land around it. A stone’s throw away to the north, the presence of the four Priddy Rings in fields pock-marked by sink holes provide a powerful connection with the underworld and ancestors, while between the two main ridges of North Hill sits an area of low-lying bog. Liminal, porous places, where water seeps into the ground, held great fascination to people throughout prehistory, and this particular bog must have been especially revered as it drains into the mysterious, vast cave system running beneath nearby Cheddar Gorge, eventually emerging from the mouth of the canyon as a rushing stream that, given its spectacular backdrop of limestone escarpments, must have seem a great wonder to the area’s ancient inhabitants.

These features explain why the two parallel ridges of North Hill hold lines of impressive burial mounds. Amid the one to the south (known as the ‘Priddy Nine Barrows’) a team of archaeologists, led once again by Jodie Lewis, recently discovered vestiges of an early Neolithic causewayed enclosure. The linear cemetery on the opposite, north ridge (the so-called ‘Ashen Barrows’), seems, when viewed from the air, to be aligned with a prominent outlier of the Mendip Hills, Crook Peak.

Travelling around this windswept upland, the twin rows of barrows often appear unexpectedly silhouetted on hillcrests – evocative reminders that the old droveways, tracks and heaths up here have been in continual use for 6,000 years, and in some cases, considerably longer than that.

Access

Drive northwest from Priddy’s ancient village green along Nine Barrows Lane until you see a small layby on the right-hand side. A public footpath leads from it to the Ashen Barrows - a more intact line of mounds than the one to the south.

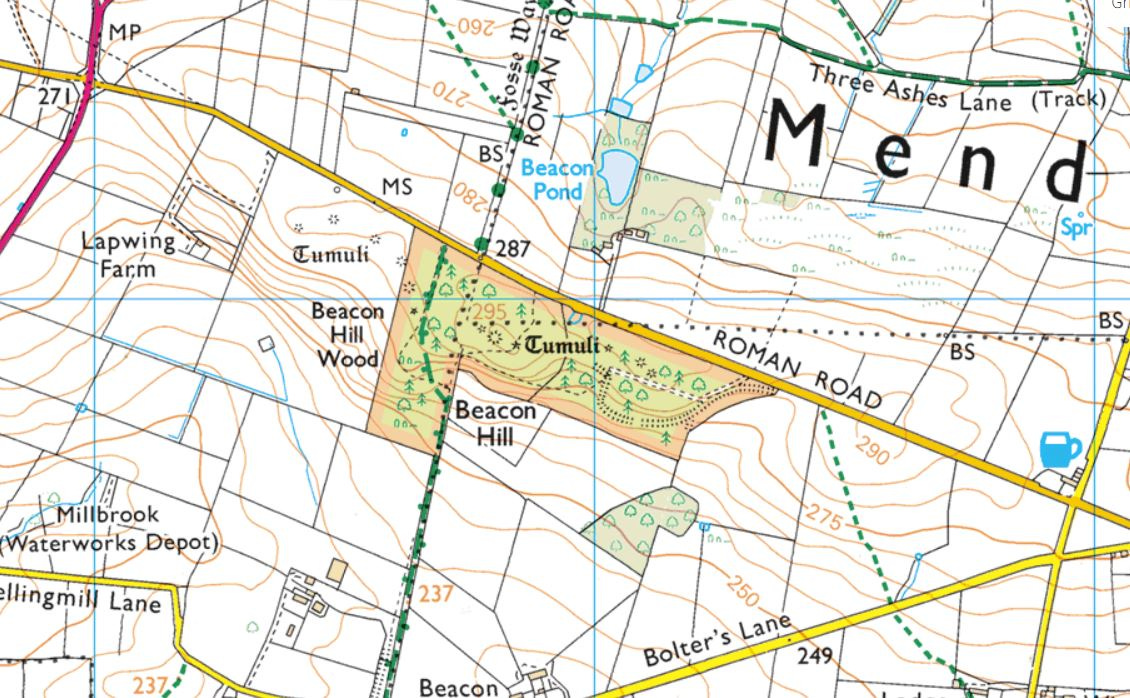

Beacon Hill

I must have driven past this fantastic site on the southeast side of the Mendip Plateau a hundred times, but didn’t realise its archaeological significance until very recently, when I stopped to take a closer look at a trio of round barrows in a field just off the old Roman lead road running past it. The spot seemed at first glance a typical but rather modest Early Bronze Age cemetery, with wide-ranging views across the Levels of Glastonbury and beyond - just the kind of place our Beaker ancestors loved to inter the cremated remains of their loved ones. What I didn’t appreciate was that the woods adjacent to the pasture held a bumper crop of nine more mounds, overgrown with trees and shrouded in undergrowth.

Four-thousand years ago when they were constructed, these tumuli would have risen from open heathland - a fact confirmed in 2007-2008 by a team of archaeologists led by Peter Leach, who excavated one of the largest barrows and found it was built of turf stacks made predominantly from heather and sedge. The turves showed signs of having been charred, suggesting the plants had been burned to promote the growth of green shoots for feeding livestock.

The standout discovery of the dig, however, was an cremation urn of the ‘Deverel-Rimbury’ style (pictured above), dating from the Middle Bronze Age, which had been inserted in the original barrow. The style of pottery is one more commonly found on the Wessex chalklands to the southeast, reinforcing the idea that the Mendips was a kind of cultural crossroads during this period. It has also been suggested the woman whose remains it held may have been from the Cranborne Chase area.

One one other pot from Beacon Hill has survived: a Collared Urn from the Early Bronze Age (circa 2,100 BC), thought to have been unearthed by a local antiquarian in the early 19th century and now residing in Birmingham Museum.

Thanks to the dense woodland enveloping the hilltop, which was planted by the Forestry Commission in the 1950s (their ploughs did terrible damage to some of the mounds), it is not immediately apparent why this spot was particularly favoured by Mendip’s herders in the Early Bronze Age. But wander around the muddy paths and you’ll come across a heavily overgrown escarpment forming a steep buttress to the hilltop on its southern side. Not only would this have created a much better outlook for the cemetery, but the rock outcropping around it - a rare form of diamond-hard sandstone similar to the sarsen used to build the Stonehenge trilithons - would also probably have distinguished this land.

When they ran up against it in the first century AD, the Roman engineers constructing the Fosse Way had to build a dogleg around the outcrop, presumably to avoid the scarp and hard rock it held. You can still clearly trace the line of the old Roman road as it veers around the hilltop then regains its original route once beyond it. Later, the Romans returned to quarry the stone for making querns, or grindstones, examples of which have turned up in many of the region’s Romano-British sites.

Access

Beacon Hill woods are nowadays owned and managed by the Woodland Trust, who maintain the parking layby and network of paths running around it. Access is free and there’s an informative panel at the entrance showing the location of the barrows and other features of interest.

Maesbury

This is the largest and most intact Iron Age hillfort on Mendip, and one affording fine views across the Levels and westwards to the Bristol Channel. It sits on the southern edge of the plateau above Wells, near the Mendip Golf Club. Access is most easily gained via the public footpath approaching it from the south.

Charterhouse

At the top of Cheddar Gorge, near a combe known locally as ‘Velvet Bottom’ near the hamlet of Charterhouse, lie the remains of old Roman lead mines. The presence of an Iron Age fort (the outlines of which are clearly visible on the left of the photograph above) suggest mining was being carried out here well before the arrival of the legions in the mid AD 40s, but production was radically intensified within six years of the Conquest. Vast quantities of metal were exported from the site, whose output at one time accounted for the majority of lead used to roof the imperial capital, Rome.

Several lead ingots, or ‘pigs’, have been discovered in the area, stamped with letters indicating their place and period of origin. One is displayed in Wells Museum; another in the Museum of Somerset, Taunton.

The square earthwork appearing in the field on the right of the photo is the footprint of the Roman fort. A circular amphitheatre may also be seen nearby.

Museums

Finds from archaeological sites across the Mendip Plateau are housed in various local collections. Bristol Museum & Art Gallery holds the wonderful Pool Farm Cist (pictured above), a slab extracted from an Early Bronze Age burial mound near West Harptree, to the north of the Priddy Circles. The grave held the cremated remains of an adult aged 30-40 years old and a 3 to 8-year-old child, radiocarbon-dated to 1980-1765 BC and 1920-1735 BC respectively. Quite what this rare piece of Middle Bronze Age art signifies is a matter of conjecture. Only one comparable example, found on Merseyside, exists in the UK, though similar pieces have been discovered in Scandanvia.

Wells Museum is the place to see the cream of the Palaeolithic and Mesolithic finds extracted from Gough’s Cave, while the Museum of Somerset in Taunton holds a fine array of Neolithic polished stone axes and an extremely rare carved wood figure discovered on the nearby Levels, as well as an impressive collection of Bronze Age items and exotic animal remains from the famous Banwell Bone Cave.

News

I’m delighted to announce that my exhibition at Salisbury Museum opened on January 20th. Featuring 22 works, including five enormous composite prints of over a metre wide, the show brings together some of my favourite aerial views of the past few years, with subjects ranging from Neolithic causewayed enclosures to Iron Age hillforts such as these beauties (from left to right: Badbury Rings; Barbury Camp; and Old Sarum). The exhibition runs until May 22nd. Please do drop by.

Work on my book is nearing completion now. Thames & Hudson have done a fine job on the layout. We’re just waiting for a break in the weather in the Orkney Islands to shoot the final sites and it’ll be ready for printing. Here’s a sneak preview, showing the spread on Bryn Celli Ddu in North Wales. I’ll be sending out information on how to pre-order copies once we know what the precise publication date will be.

Once again, thank you everyone for your support over the past few months. It was great to meet so many of you on Alice Roberts’ Ancestors tour in November, which I greatly enjoyed despite the problems I was having with my old ticker at the time. I’m sorry I wasn’t able to keep up my monthly newsletters but I hope you’ve enjoyed this and will find inspiration in the extra ones I’m planning for weeks to come.

David

Many thanks, excellent update