Unseen Stonehenge

A roundup of the most spectacular monuments around the great stone circle, which you can visit for free….

It’s the middle of the night, in the depths of winter. The thermometer in my van reads 8 degrees below as I slide the door shut and set off down the lane. Salisbury Plain lies under a dusting of snow, its undulating expanse sprawling southwards like a moon-lit desert as I emerge from a tunnel of trees to open pasture. Ice crystals glint in the beam of my head torch, my boots crunching in frozen puddles shattered earlier by gangs of excited children from the nearby army camp.

I’d decided to walk the Greater Cursus to help stave off hypothermia while I waited for sunrise. But the experience proved so hypnotic and so compelling I carried on for what must have been hours, following the shadows of the Neolithic banks as they scythed across the grasslands to the long barrows in the distance. Every so often I’d pause to light a bundle of sage, enjoying the glow of the embers and fragrant smoke as it rose into a windless sky, or to pour hot tea from my flask, or to watch the moon sinking behind a coppice of beech trees on the horizon.

No conclusive date has been established for the great earthwork I was following, but a few fragments of red deer antler unearthed in it were carbon dated to 3770–3660 BC – six or seven centuries before the first circle was dug at nearby Stonehenge, and over a thousand years before the arrival of the big sarsen stones. Nor does anyone really know how the Cursus was used or precisely why it was built. The fact its squared ends enclose a pair of much older chambered tombs suggest it may have been connected with funerary rituals, but no-one can say for sure.

Walking around the monument on a midwinter’s night, though, underlined what an immense undertaking it must have been for our ancestors. Construction on this scale, involving hundreds of people and a high degree of social organization, had never been undertaken before in these islands, which begs the question of why they went to such trouble?

The Greater Cursus may conceivably have followed a route sacred to the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers who erected large timber posts on this plateau centuries before (close to the site of Stonehenge itself). But unlike the strident, almost triumphant circle of megaliths just across the fields, the over-riding feeling here is one of doom. To me, the Cursus feels like a giant act of desperation. It was quite literally the Biggest Thing our ancestors could do with the technology available to them at the time, involving months, or years of back–breaking toil. But why did they do it?

A clue may lie in the soil. Mollusc and pollen analysis have shown that woodland clearance in southern England stopped at roughly the time the Greater Cursus (and its smaller cousin, the Lesser Cursus nearby) were built. Neolithic communities appear to have deserted their traditional territory and given up cereal cultivation in favour of nomadic pastoralism on the uplands. Population also appears to have dropped.

One explanation for the so-called ‘Neolithic Collapse’ is that a marked decrease in solar activity around this era may have led to a fall in average temperatures. Another posits a connection with the demise of the Neolithic Yamnaya ‘mega-settlements’ of Eastern Europe in this period, which some researchers now believe may have been the result of the world’s first pandemic. Traces of the bacteria Yersinia pestis, an ancestor of the microbes responsible for bubonic plague, have been found in numerous Neolithic graves. Could it be that this same pathogen was having an impact on the inhabitants of Salisbury Plain, and that the Greater Cursus was an attempt to halt the spread of disease by placating or appeasing the gods?

The answer may never be known in our lifetimes, but this vast etching on the surface of the Plain certainly warrants a detour if you’re visiting the stones – ideally at the start or end of the day, when its contours emerge most vividly from the shadows.

Walking the Cursus

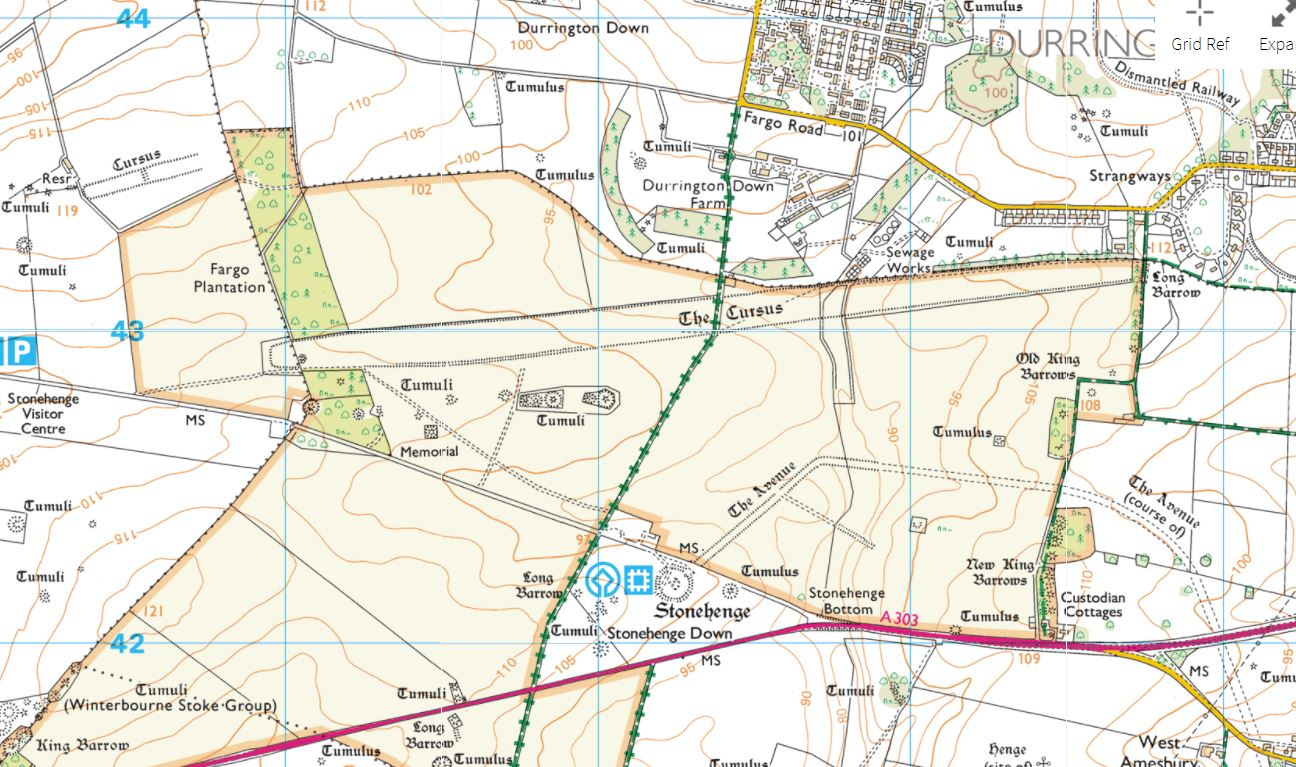

The easiest way to access the earthwork is via the military camp at Larkhill. Follow Willoughby Rd south past the health centre for around half a mile until it reaches Fargo Rd. You can park up there and continue on foot south along the bridleway (in the direction of Stonehenge), which crosses the Greater Cursus after a five-minute walk: look for the information panel beside the fence.

The Kings’ Barrows

The eastern end of the Cursus rises to a low ridge studded with ancient burial mounds, including an early Neolithic long barrow. The show stealers here though are a line of half a dozen enormous bell barrows dating from the Early Bronze Age (roughly 2,500 BC, corresponding to the third and final phase of Stonehenge).

They mark the spot where the Avenue leading from the River Avon to the stone circle crosses the ridge, which today holds a coppice of yew and beech trees planted in the 18th century. When a few of these trees blew over in the great storm of 1987, the resulting damage revealed the mounds were not made of compacted soil but turf stripped from the surrounding pasture. As estimated 18 acres (7.2 hectares) of land would have had to have been peeled clean to build them. Was this a symbolic more than a practical act perhaps? Burying a loved one under a blanket of turf torn from sacred ground would certainly have had resonance for the herders whose flocks grazed these uplands 4,500 years ago.

Normanton Down

Literally hundreds of barrows rise from the fields around Stonehenge, underlining the extent to which the stone circle remained a place of great sanctity for the ‘Beaker People’ who replaced the region’s Neolithic population in the second half of the third millennium BC. Named after the distinctive long-necked urns found in their burial mounds, these incomers brought with them knowledge of metal, ushering in the Bronze Age to Britain. With roots in the distant Pontic-Caspian Steppe, they were the descendants of nomadic herders from the great grasslands of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, who later settled in what we now know as Belgium and Germany.

The most famous barrow cemetery of all lies a mile to the south of Stonehenge on Normanton Down. Reached from the A303 via a rutted bridleway today, it includes a collection of forty differently configured mounds enclosing the remains of what we must assume were high-status individuals (both men and women) from the latest phase of Stonehenge, around 1,900–1,700 BC. Many yielded spectacular grave goods, but one barrow in particular has become illustrious in the annals of archaeology for its collection of sumptuous artefacts, which included a gold lozenge finely inscribed with a hexagonal pattern. A belt of sheet gold, three bronze daggers, a bronze axe and a richly carved stone macehead made out of fossilised sea sponge were also discovered by Richard Colt-Hoare when he dug into the barrow in 1808. All are now displayed in the Wiltshire Museum, Devizes.

I’ve visited the site several times – always at dawn, when the nearby highway is quiet and the low light accentuates the contours of the mounds. Only from the air, though, can the spectacular way the barrows were arranged be fully appreciated.

To me, these ancient cemeteries on Salisbury Plain are as poignant as they are impressive. Judging by the effort and care that went into their construction, they appear to have been created in a spirit of love and respect, not merely a desire to impress and underline social status. Silhouetted on high ground overlooking Stonehenge, they always inspire a sense of drama and anticipation, reminding us that we’re entering a realm apart where for thousands of years our forebears venerated their forebears. It seems only natural that we should do the same, yet these dignified, mysterious memorials rarely attract much attention.

Winterbourne Stoke Crossroads

The low, broad ridge to the west of Stonehenge holds a particularly high concentration of barrows, the biggest of them around the Winterbourne Crossroads, where the A360 to Salisbury intersects the busy A303. This spot was revered long before the stone circle was erected: a huge long barrow dating form the early Neolithic period was the first monument built here. It was followed by a row of enormous Bronze Age burial mounds, aligned with the original Neolithic tomb. Unlike those at Normanton Down, though, these are easy to reach: park at the layby on the A303 and follow the public footpath sign through the birch woods for two minutes.

Winterbourne Stoke East and The Coniger

A much less well known, but beautifully situated Bronze Age cemetery lies a twenty-minute walk north of Winterbourne Stoke village. Known as ‘Winterbourne Stoke East’, it sits on the western edge of Fore Down, overlooking the secluded valley of the River Till – an idyllic spot still today. Mounds of various sizes, including a particularly large saucer barrow some 10 metres in diameter, lie within a bank-and-ditch enclosure. Visible on the opposite side of the valley, at roughly the same height, is a second enclosed cemetery known as ‘The Coniger’, which holds six different types of barrow. One of them – a disc barrow – was found by Colt-Hoare to contain two Saxon cremations wrapped in cloth and accompanied by an iron dagger.

Museums

On display at the Stonehenge Visitor Centre are numerous items unearthed in the monuments of the area, but the most impressive collections are in the region’s two largest museums. At Devizes, the Wiltshire Museum is home to the Bush Barrow Lozenge and other treasures from the illustrious ‘Wessex Burials’ investigated by antiquarians William Cunnington & Richard Colt-Hoare in the early 19th century, including a magnificent turquoise jadetite axe that was allegedly used as a paper weight by its owner in Georgian times, while Salisbury Museum, opposite the cathedral, is custodian of the Pitt-Rivers Collection of antiquities, among them an outstanding array of Beaker burial urns and grave goods. The latter’s ‘Wessex Gallery’ is also where you can see the skeleton of the famous ‘Amesbury Archer’, among the richest Beaker graves ever discovered, dating from the dawn of the Bronze Age in southern Britain.

News

I’m delighted, and amazed, to have raised over £15,000 through my Crowdfunder campaign. Around 60% will go towards fulfilment (to cover the cost of books and postage), but the remainder, I’m relieved to say, will be enough to see me to the end of the project. My publishers, Thames & Hudson, also generously shunted forward the second instalment of my advance. So the pressure is off for a while . . .

Thanks to all of you who pledged. Without your support my attempt to cover the more remote corners of the Scottish Highlands and Islands would be stalled now.

I had another bit of good news last week: Salisbury Museum have agreed to host a major exhibition of my work from next January. We’re very excited at the prospect of printing up and framing some huge pieces for the show, including the long, rectangular Cursus Barrows composite featured above. I can’t imagine a more appropriate place to do it than their art space, which is right next to the fabulous Wessex Gallery, with its collection of prehistoric wonders from the Plain and environs.

Thanks for reading my first newsletter. I hope you enjoyed reading it, and look forward to getting the next one together soon.

A great read and visual treat. Thank you

I hadn't heard that theory about the cursus before - fascinating stuff!